The Quality of the Transitory

The Matters of Activity Cluster of Excellence focuses on a new material culture

Dec 12, 2019

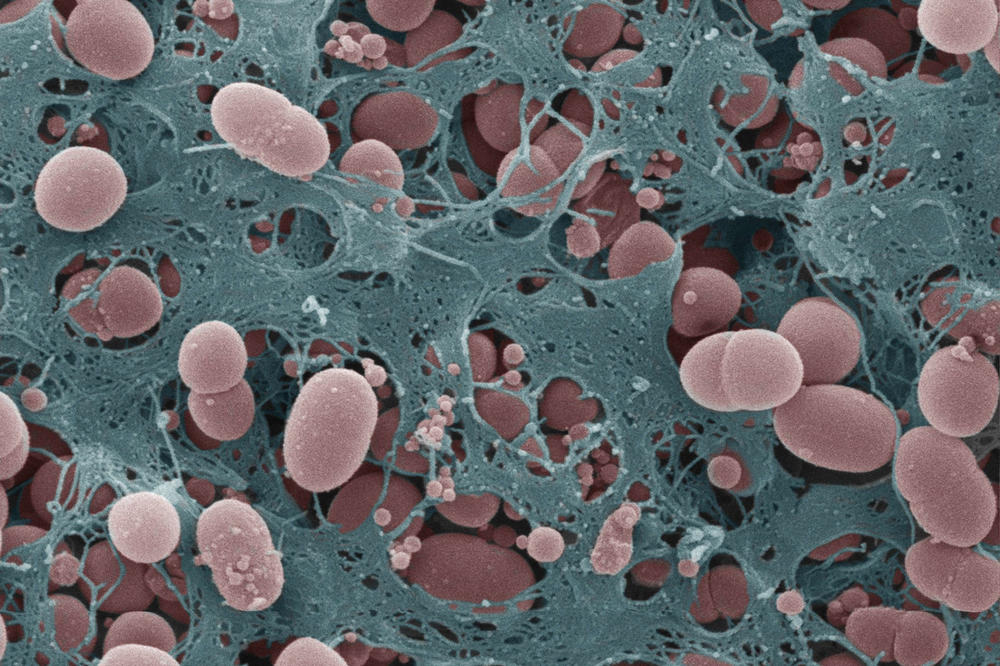

Adaptive microstructures: In biofilm, bacteria build fiber architectures with special material properties, which are being investigated in the cluster.

Image Credit: Diego O. / Regine Hengge

The idea of separating body and mind cannot be translated into a product more consistently: In the Silicon Valley of the 21st century, the mind, as it were, has gotten rid of the body, and algorithms “live” without an expiration date on constantlywearing hard disks. This model of immortality seems so tempting to some that a start-up company now even wants to transfer it to the human being, the human brain, or rather: its thought activity, by uploading it to the cloud. The body as carrier material of immortal information, arbitrarily interchangeable, or even completely superfluous?

A radically different view of the world of matter can be encountered on Sophienstraße in Berlin-Mitte. The premises of the Matters of Activity Cluster of Excellence, which started its work in January 2019, are located here. Even the name itself shows that here, matter is not seen as something passive that has to function according to an external will and is scrapped in the event of failure, but as something that is governed by its own laws, whose impulses are affirmed and regarded as productive.Wolfgang Schäffner, a Professor of Cultural History of Knowledge at Humboldt-Universität in Berlin, is the spokesperson for the new Cluster. He understands Western postmodernism, whose view of the material he and his comrades-in-arms want to change, as shaped by a culture of conservation. “Change is not intended in our present culture of materials, so the activity of a material is usually to be switched off. A table made of wood should remain exactly as it is and not come apart at the seams over time; iron corrodes, you need corrosion protection.”

Stopping aging processes in favor of an ideal of rigid immortality – in a universe striving for disorder, this is a futile struggle. By contrasting the European attitude with an example from the Far East, the philosopher, literary scholar, and medical historian demonstrates that artefacts can also be thought of quite differently. “Like many other buildings in this country, Japanese shrines are protected, but are demolished every 20 years and then rebuilt,” reports Schäffner. The researcher refers to a tradition within the framework of the natural religion Shintoism, which, in contrast to most European traditions of thought, focuses on the here and now. “Over there, it is the building process that is preserved, while we preserve the objects of the past themselves like corpses.” A culture of embalming that, at least symbolically, tries to trick death?

Sustainable: Natural materials operate in an energy-efficient manner

Wolfgang Schäffner locates the historical origins of the tendency toward overly durable products above all in the 19th century. “This was the time of railways, mechanics, concrete and steel, of passive, hard, and rigid materials.” Principles of that time were also applied in the 20th century and, according to Schäffner, are still adhered to today. This includes the use of materials that are difficult to recycle and that often consume an excessive amount of energy during production. Material here was considered to be exclusively passive and would have to “be kept still with a control device, like a slave. That ignores an intelligence that is inherent in thematter itself, and thus consumes an extreme amount of energy.”

This means that the impact of environmental factors such as solar radiation, humidity, and temperature fluctuations is prevented at a high cost in such designs. Today, such product design ideas are the basis of a global industry whose profits are growing every year. This is disastrous not only with regard to the constantly growing mountains of plastic waste. “To give a concrete example of this thinking in production: the car is the legacy of the railway, a historical legacy that we carry around with us. We build something that weighs a ton in order to move an object weighing less than 100 kilograms,” emphasizes Wolfgang Schäffner, shaking his head. “And on top of that, it was never meant to be a mass product.”

It can only be said that current technology has lost the game in terms of design from the outset. In terms of engineering technology, there is a lot of know-how behind it. But Matters of Activity thinks in a completely different direction. Whereas people still like to pour designs into concrete, natural systems usually work with degradable, adaptive materials.

Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Schäffner is the spokesperson for the "Matters of Activity" Cluster.

Image Credit: Matthias Heyde

“Thingsmay not go as fast in nature as they do in an airplane, with wood you may not be able to built quite to high, but it’s much more sustainable in terms of energy,” says Wolfgang Schäffner. Highly complex structures in biological systems are often achieved by the architecture of a single material which can be adapted as required, such as a fibrous material like cellulose.

The research team wants to investigate such materials and systems, the processes of weaving, cutting, and filtering that take place on and inside them, to better understand their functionality and investigate their adaptability in order to develop alternatives with regard to traditional object design.

A particularly impressive example of an adaptive process being investigated in the cluster is biofilm. This consists of a slimy layer in which microorganisms of different types or the same type live, communicate with each other via chemical signals and, depending on the situation, collectively adapt their behavior. Thus, the microorganisms protect each other from starvation or help each other in the fight against attackers.

Almost no watery surface – whether incisor, washbasin, or forest floor – is safe from the lightning-fast formation of such composites. Three-dimensional structure and growth of biofilms depend entirely on the specific environmental conditions. Due to their structural complexity, they cannot yet be described mathematically. “Even a small number of bacteria can build structures that overburden our previous ideas of code and intelligence,” Schäffner sums up, thus demonstrating the great potential of corresponding basic research.

So far, the intelligence of systems has always been outsourced to digital controls. “In nature, however, there is no such separation of work and operational entity. In every wooden structure, in every leaf, there is code – not just in the DNA.” Structure and function connected here cannot be separated from each other. The aim of the cluster is to make the analog visible in its trans-digital quality. “Our challenge today is called the Anthropocene. The optimum that we as a global community can achieve in the future is to replace conventional artefacts with equivalents of degradable substances such as cellulose or sugars and thus avoid the further formation of mountains of waste that can no longer be recycled.” The cluster hopes to bring the world one step closer to this optimal future with basic interdisciplinary research on the structure and composition of such transient materials.

Further Information

Matters of Activity

At the Matters of Activity cluster researchers from more than 40 disciplines are working on six subprojects to establish a new way of thinking about materials. The central vision is not to conceptualize material objects as passive and rigid as has most often been customary so far, but rather to think of active, changeable, and recyclable building materials. Fibers and complex biological systems are among the sources of inspiration for possible designs of the future. The cluster's ideas are as close to those of the Bauhaus as they are to the academic movement of New Materialism.