Water is scarce and becoming scarcer – solutions for Berlin-Brandenburg

Irina Engelhardt conducts research on groundwater resources in Berlin-Brandenburg and coordinates the interdisciplinary project SpreeWasser:N.

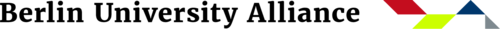

Drier summers, falling groundwater levels, growing cities – the situation in Berlin and Brandenburg is coming to a head. The region is already one of the hottest and driest in Germany. At the same time, water demand is rising: agriculture, industry, and households are increasingly competing for what comes from the soil and rivers. The situation is particularly critical on the Spree, because the phase-out of lignite mining in Lusatia will eliminate decades of inflow from drainage water. This has massive implications – the Spree, previously one of Berlin's most important sources of water, is threatened by low water levels in summer, reverse flow, and in some cases complete stagnation.

This is where the large interdisciplinary research project SpreeWasser:N comes in. It aims to develop practical ideas on how water can be better distributed, used, and protected in Berlin and Brandenburg. The goal is to create helpful tools, strategies, and good examples for sustainable water management.

Prof. Dr. Irina Engelhardt heads the Department of Hydrogeology at TU Berlin. Together with her team, she wants to analyze not only how water is distributed in the region, but above all how it can be stored more sustainably. Her approach: holistic water management that combines disciplines, involves regional stakeholders, and researches technologies such as artificial groundwater recharge.

Irina Engelhardt was recognized for her work in our ideas competition in the “Climate and Water” category. In this interview, Irina explains what motivates her and why water is everyone's concern.

Measuring devices above the water – a visual interpretation of Irina Engelhardt's research. The motif will be displayed on posters throughout Berlin as part of the BUA OPEN LAB campaign. | Artist: Liam Schnell

Dear Irina, congratulations on winning the BUA ideas competition in the field of climate and water. What motivated you to take part in the ideas competition?

The topic of water is very important to all of us, and we are convinced that people outside scientific circles also have a genuine interest in learning more about this precious resource. We thought it was great to have the opportunity to reach a wide audience through the Berlin University Alliance and the ideas competition and to tell people about our water resources.

What can be seen in the picture you created with artist Liam Schnell? Why did you choose this motif?

All of the measuring devices that have been combined to create this delightful creature are our little and big helpers in determining water quantities. All in all, that is the question for us—how much water is there?

With the hydrometric measuring wing, the body, we go into flowing waters and determine how much water is flowing through the water bed based on its rotation frequency. With the cable sounder, the tail, we go to groundwater measuring points and measure directly how high the groundwater level is. The level rod arms are used for above-ground water level measurements in rivers and lakes. And of course, there are the two water-filled vessels, the sample vessel and the round flask, to also determine the quality of the water.

The motif is essentially an all-round measuring system that beautifully visualizes how our field research is conducted.

What are the main problems currently facing the Berlin-Brandenburg region in terms of water supply?

The Berlin-Brandenburg region is considered one of the warmest and driest regions in Germany. As a result, water scarcity is particularly acute here. In addition to climate-related periods of drought and increased evaporation and transpiration, socio-economic developments are also depleting the already depleted groundwater reserves. Water demand in agriculture, industry, and private households is growing in line with population growth and increased consumption on particularly hot days.

It is important that we also address the phase-out of lignite mining in the Lusatian mining area. For decades, drainage water from lignite mining was discharged into the Spree River, which continuously and artificially increased the river's water flow.

The Spree is one of the most important sources of water in our region. With the phase-out of lignite, a water source is becoming a water sink. Especially in the dry summer months, we will be confronted with challenges such as low water levels in ecologically critical areas, reverse flow directions, and in some cases, the complete stagnation of the Spree.

In short, the “thirst for water” is already great and continues to grow, while the water supply is scarce and becoming scarcer.

The SpreeWasser:N project is conducting research into “integrated water resource management” – what does that mean?

For us, integration means combining different areas of research, upholding sustainability as a guiding principle, and taking a participatory approach. This holistic approach enables us to address specific issues relating to water resources in the Lower Spree region. Our calculations and forecasts take into account a wide range of aspects of water resources, from climatic changes and geological structures to legal frameworks.

Involving stakeholders from the region is important to us because, ultimately, we are working on solutions for them and they are best placed to give us feedback on their specific circumstances. At the same time, we aim to ensure that our products and proposals have an impact beyond the project period and are accepted by as many users as possible.

What aspect are you working on at TU Berlin?

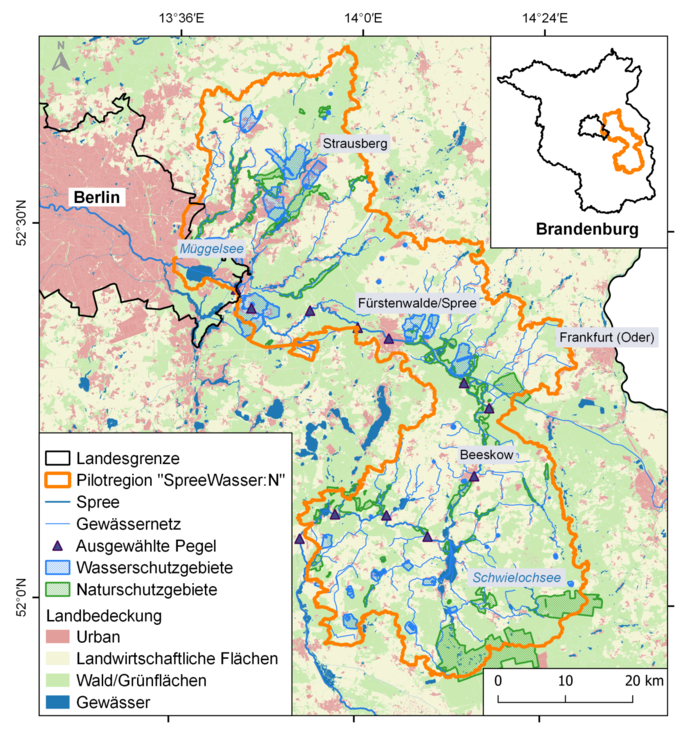

In addition to project coordination, we are focusing our efforts on groundwater. As part of SpreeWasser:N, we have developed a 3D geological structure model and, based on this, a groundwater flow model for the Lower Spree model region.

These models enable us to look sharply into the subsurface. We ask how, where, how fast, and whether groundwater flows in the different aquifers. We are currently determining how old the water is and monitoring groundwater levels in field measurements. At present, for example, the water for drinking water supply in Brandenburg is primarily extracted from the second aquifer. This water was formed approximately 50–100 years ago. Groundwater droughts lead to withdrawals from deeper aquifers and older water. On the one hand, these are finite resources and, on the other hand, older water also has different chemical properties, which in turn may require treatment measures.

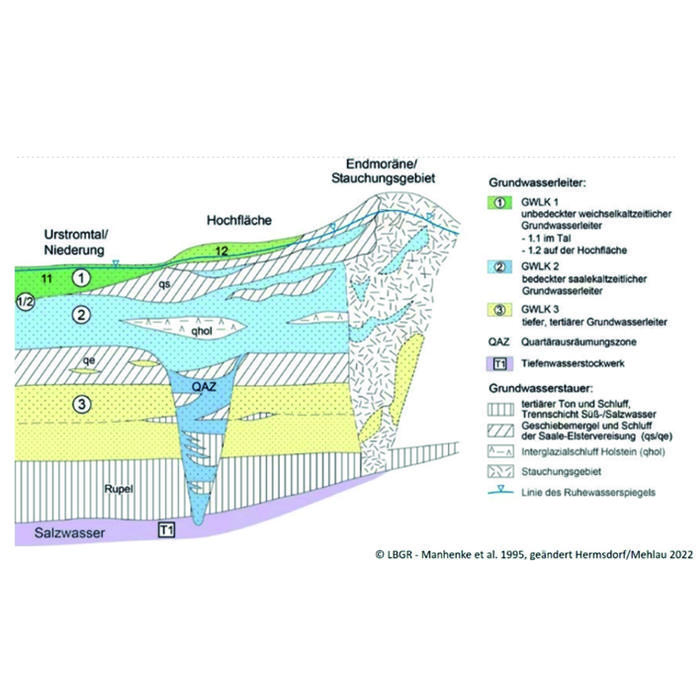

In your project, you outline ways to artificially enrich groundwater. How is this done?

One of our proposals for limiting the groundwater problem in the long term is managed aquifer recharge (MAR), i.e., artificial groundwater recharge. We analyze where and when water can be extracted from surface waters and then stored in underground aquifers using the appropriate infiltration method. Heavy rainfall deserves particular attention in this context. Sometimes, precipitation water leaves the model region's system as base and intermediate runoff without contributing to groundwater recharge. This is due, among other things, to impermeable layers of rubble soil in the ground.

In artificial groundwater recharge, excess water is fed into the aquifer via injection wells, from which it can also be extracted again as needed. Credit: Dr. Ata Joodavi

We can circumvent this problem by constructing deep injection wells. The excess water is fed into the aquifer through the wells, from where it can then be extracted again as needed. In this way, we contribute to groundwater recharge on the one hand and to fundamental water security on the other.

How realistic is the use of such technologies in Berlin and Brandenburg?

With regard to the feasibility of MAR, it should first be noted that the storage of water in the aquifer is legally permissible in principle, but requires official approval. Approval is subject to strict water law regulations and is linked to the requirement for chemical water treatment. In Berlin and Brandenburg, we are often faced with a lack of responsibility.

What does your research mean in concrete terms—will we have to use water more sparingly in the future?

The scale of the water problem is too great to be solved by water conservation in private households and garden irrigation alone. Our research first provides spatially and temporally high-resolution forecasts for the occurrence of water scarcity. This enables water managers in water-intensive sectors such as industry and agriculture to adjust their water resource planning at short notice. The second pillar of our research is storage. It's not just about using water wisely, but also about using what we have available as efficiently as possible.

The forecasts underlying your research topic are quite bleak overall. What gives you hope that we humans can learn to use water resources more consciously?

Farmers and landowners from the Spreewald region have already approached us to obtain information about water retention options. Water extremes are now so commonplace that we tend to encounter interest in our work.

The SpreeWasser:N project brings together many partners. How does working across different disciplines and institutions work?

From the outset, we were very interested in setting up the project on a broad basis in order to address as many aspects of the water cycle in the Lower Spree model region as possible in as much detail as possible. It can sometimes be a little tricky to bring partners who are highly specialized in their respective fields back from their more global perspective to our pilot region. Essentially, however, it is precisely this comprehensive knowledge that benefits our project. Collaboration across disciplinary boundaries greatly enriches the discourse in our working group – even if the lively discussions can sometimes go on for a very long time.

Dear Irina, thank you for the interview!