Mathematics for a better future

How simulations of millions of synthetic humans can accelerate the transport transition

We are living in a time of major transformations - the sustainable transformation of mobility is one of them. Anyone researching this issue has to deal with complex social systems, technological and political aspects, different interests and many other variables.

How can we get to grips with this complexity? A method with an unwieldy name comes to the rescue here: agent-based modeling. This is not about spies, but about mathematical models that simulate the behavior of many individual actors, so-called agents, and investigate how their interaction affects an overall system.

This type of application-oriented mathematics is one of the methods used by the Berlin Cluster of Excellence MATH+. The aim is to develop new approaches in this area - across institutions and disciplines.

Dr. Sarah Wolf (FU Berlin) and Prof. Dr. Kai Nagel (TU Berlin) are researching agent-based models at MATH+ and are in demand both in school classes and among decision-makers. Their work is an inspiring example of research in the open knowledge lab Berlin, which does not take place behind closed doors, but in exchange with the people of the city!

The MATH+ campaign motif: The “Math Agent,” originally from the comic “Ida and the Math Agent,” embodies a mathematical model. Here with Sarah Wolf and Kai Nagel at Potsdamer Platz. © BUA

Mrs. Wolf, Mr. Nagel, in the MATH+ campaign motif, a math agent sits on the historic traffic lights at Potsdamer Platz and has to choose between different modes of transport. Why not an agent?

Sarah Wolf: For me, agent is a neutral word, like table. Because our agents are mathematical elements or objects in the computer. They can take on very different roles.

Kai Nagel: In mathematical language, an agent is the description of an acting person who has an internal state and follows certain rules of behavior. With a large number of such agents, we can ultimately simulate a society in the computer, within certain limits of course.

What properties can such an agent have?

Wolf: A colleague always explains this to school classes: "Shoe size and your favorite movie are not important when it comes to mobility, but age, income, place of residence and work, health and even political views are.

Do you also work with school classes?

Wolf: Yes, we combine the agent simulations with an element of citizen participation, for example for schools. The technical term for this is transdisciplinarity, but the BUA campaign's catchphrase “open knowledge lab” would also be very apt.

Nagel: We organize workshops in which people can make political or administrative decisions themselves and then immediately see the effects of these decisions through our simulations. Our topic here is transportation planning.

The aim of these workshops can be to get ideas, for example for new measures. Another goal can be to provide the actual political decision-makers with packages of measures that a large majority of people in our workshops have endorsed.

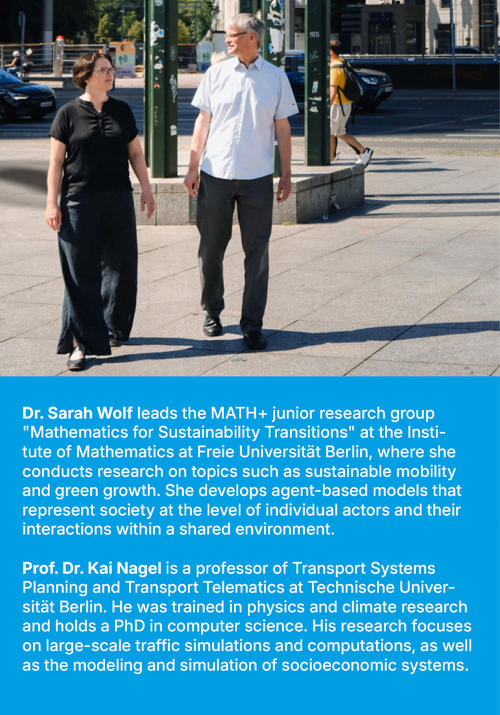

Spread of COVID-19 infection in Berlin based on a simulation model (MATSim-EpiSim): Place of residence of individual residents, color-coded according to their infection status over time. © Kai Nagel

During the corona pandemic, the results of your simulations were already the basis for political decision-making, Mr. Nagel.

Nagel: Yes, my department at the TU Berlin simulates people's mobility behavior using anonymized mobile phone data with the help of agent systems, among other things.

During the corona period, we were able to see how often people meet, how they use public transport and so on. From this, we estimated both the infection rates and the likely impact of coronavirus protection measures.

In this context, we used the MATSim-EpiSim model, which can simulate epidemic outbreaks, to create an interactive visualization of a possible outbreak scenario: a 90-day time lapse that shows the place of residence of individual residents and their infection status over time.

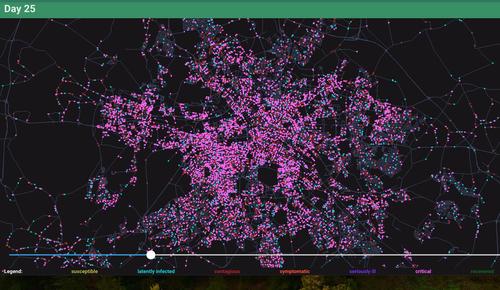

“Decision Theater” with four large screens. Here, the effects of the measures decided upon after the group discussions are displayed, such as increases or reductions in emissions. © Beate Rogler / MATH+

How exactly do your workshops work?

Wolf: Kai Nagel and I use slightly different formats. I use what is known as Decision Theater, which was originally developed in the US. In our case, 15 to 30 people discuss ten different options for a mobility transition in Germany in small groups. These include purely political measures such as bans, but also possible investments and assessments of future developments.

Specifically, participants must decide, for example, whether to make public transportation more affordable or invest in charging stations for electric cars. And what do we think: Will they soon become cheaper? Can we more easily combine public transportation and rental vehicles through digitalization?

The groups must make a selection by answering questions on a tablet. We then look at the corresponding results of our agent simulations with these different inputs and can discuss the effects in a plenary session.

So we take a look at various possible futures that reveal some surprising consequences of the participants' decisions. For example, when subsidies for electric cars mean that public transport is no longer used because even environmentally conscious people are now buying cars.

Shouldn't such workshops be made mandatory in the work of the Bundestag? Wouldn't that prevent many mistakes?

Wolf: That would be exciting, of course. But I must emphasize that we cannot predict the future like a crystal ball. The discussions in the plenary session are more about helping people recognize that things are complexly interrelated and that there are no easy solutions. In addition, everyone has to put their arguments on the table, and it often becomes clear that we actually want the same thing, but have different ideas about how the world works.

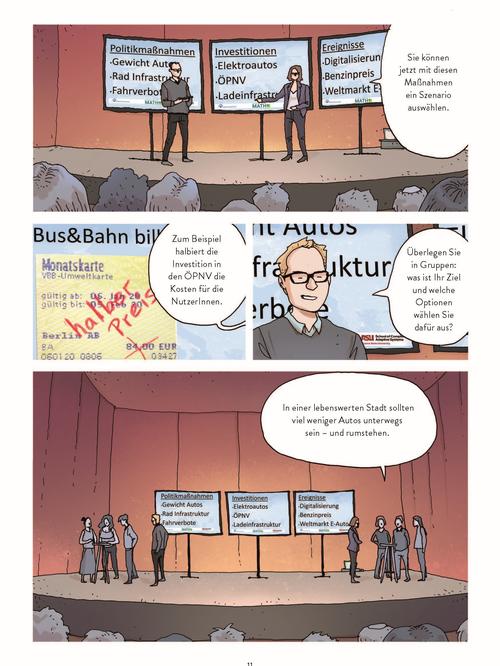

Comic zum Thema „Decision Theatre“: „Ida und der Mathe-Agent oder eine Geschichte vom Modellieren der Mobilität von Morgen“, von Sarah Wolf et al., gezeichnet von Alberto Madrigal

How does your method differ from that of Decision Theatre, Mr. Nagel?ie unterscheidet sich Ihre Methode, Herr Nagel, von der des Decision Theatres?

Nagel: We conduct what are known as citizen assessments on mobility transformation scenarios. The process is similar to Decision Theater, but we limit ourselves to traffic in the respective region, which allows us to perform more accurate simulations. We also try to ensure that the participants represent a broad spectrum of society.

What were the results of these citizen reports?

Nagel: On the one hand, there is broad consensus. More than 90 percent of participants support the goal of non-fossil fuel transportation by 2045. More than 80 percent also favor the polluter pays principle. However, when it comes to specific measures such as tolls or more expensive resident parking permits, approval drops to below 50 percent.

Can you derive specific recommendations from the citizens' reports?

Nagel: One result is that commercial transport can be made CO2-free by technical means, and this is not particularly controversial – so progress could be made more quickly in this area.

The area of private passenger transport is particularly controversial. So-called pull measures such as the expansion of public transport or cycle paths enjoy broad support here, but they will not be nearly enough to make private passenger transport CO2-free.

If the goal is “only” to achieve CO2 neutrality, the engines of the many remaining vehicles would also have to be decarbonized; if, at the same time, the number of cars in urban areas is to be significantly reduced, there is no way around push measures such as bans, restrictions, or price increases in all simulation runs.

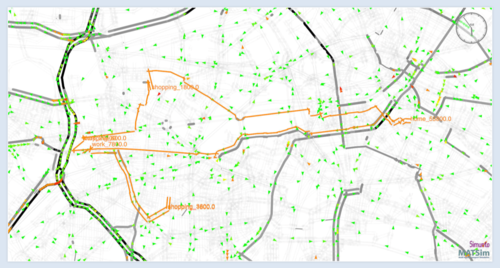

Verkehrsverlauf in Berlin: Tagesplan einer synthetischen Person in orange, Positionen anderer Fahrzeuge in grün und rot, sowie die NOx-Belastungen (Stickoxide) auf den unterschiedlichen Kanten (in grau). © Kai Nagel / TU Berlin, VSP

What characteristics and interests do you give the synthetic humans in the simulation?

Wolf: Our agents want to maximize the benefits of their mobility choices, taking into account factors such as cost and convenience. They exchange information with other agents about the benefits of different modes of transport.

Nagel: At our company, every agent receives a daily schedule with goals they want to achieve. So they drive to work, go shopping, go to the gym in the evening, or meet up with friends—just like real people. These agents are then placed on virtual city maps and assigned work locations and so on. They choose their means of transportation based on criteria such as time and cost, and the means of transportation themselves also play an active role. For example, there may be traffic jams in the model if there are too many vehicles on a road.

Where does all the data on how people behave come from?

Nagel: In fact, traffic planning consists largely of empirical social research. Data has been collected for decades, including surveys of tens of thousands of people, traffic counts, population and company registers, and psychological studies. We can test our models by creating the conditions for well-researched effects in their synthetic world and seeing whether these effects are reproduced.

You are both members of the MATH+ Cluster of Excellence. Where do you encounter particularly tricky mathematical problems in your research?

Wolf: Simulating the behavior of millions of agents takes time, and we don't have that in a one-day workshop. To solve this problem, you can keep the number of options to choose from small and simply simulate all their combinations in advance. But if you really want to be live, you have to simplify the models. One way to do this is to use molecular dynamics methods and approximate the behavior of the agents using equations that can be calculated much faster. This also allows you to respond flexibly to complex compromise proposals from participants, such as when they suggest that the parking fee should not be tripled but only doubled, and in return the bus should only run every 15 minutes instead of every 10 minutes.

Nagel: The much-maligned compromise is, in fact, the norm when it comes to democratic decisions.

Wolf: Yes, ideally, our workshops are scientifically sound compromise machines!

Ms. Wolf, Mr. Nagel, thank you very much for talking to us!

Interview: Wolfgang Richter

What else can mathematics be used for? Here are some more examples →

Unusual science communication from MATH+: The comic “Ida and the Math Agent” →